Nearly 40 years after the Watergate arrests, a former police spy has published a book in which he makes extraordinary claims about the FBI’s COINTEL program and, just as sensationally, the supposed dismantling of the Nixon Administration by a Pentagon spy-ring.

Watergate Exposed is the biography of a “Confidential Informant” named Robert Merritt, as told to one of the lawyers for the Watergate burglars. It is not a very good book, or even a very reliable one. But it may be a mistake to ignore it. Among other things, Merritt claims to have tipped off the police in advance of the June 17th Watergate break-in, to have participated with police and Pentagon agents in the drugging, kidnapping and blackmailing of a senior CIA lawyer, while also having a hand in the poisoning of antiwar demonstrators.

***

The story begins in the tradition of the bildungsroman, with the young Merritt leaving an unhappy home in West Virginia, only to wash up at a Trailways bus station in the nation’s capital. A good-looking kid with few, if any, moral inhibitions, it was apparently only a matter of minutes before he concluded a sex-for-hospitality arrangement with an employee at the bus station. With his domestic situation efficiently sorted, Merritt then went looking for more gainful employment, and soon found it as a post-mortem technician in a local hospital. His job? Removing the hearts from the cadavers of children for use in a government study.

The work seems not to have bothered him overly much. He toiled at it for two years before he found what became his life’s calling. In January, 1970, while cruising the city’s “artsy” Dupont Circle neighborhood, Merritt attracted the attention of an undercover police detective named Carl Shoffler.

No ordinary cop, Shoffler was a born conspirator, forever setting traps for the wicked. Affable and very intelligent, he was a veteran of the Army Security Agency and its “listening post” at the Vint Hill Farm station in Northern Virginia. Working closely with the National Security Agency (NSA), Vint Hill was an antennae farm whose classified mission was to intercept Soviet Bloc radio transmissions – as well as communications among antiwar organizations, radical groups and left-wing think-tanks headquartered in the capital.

To an undercover cop like Shoffler, whose official responsibilities shifted between Vice and Intelligence, Merritt was quite the prize.

Here, it should be recalled that the times were virtually radioactive. Two months before Merritt and Shoffler hooked up, more than half-a-million demonstrators braved tear-gas in the streets of Washington to protest the Vietnam war. Soon afterwards, college students were gunned down by National Guardsmen on the campus of Kent State University. The antiwar movement, already white-hot, exploded. So did the Army Mathematics Research Institute at the University of Wisconsin, where a cabal of students and townies detonated a van-load of ammonium nitrate fertilizer, inadvertently killing a graduate student who was working late that night. In Washington, the Weather Underground detonated their own bomb – inside the Capitol itself. Student riots became routine throughout the country, and to many people – Left, Right and Center - it seemed like the wheels were coming off.

All of which combined to make Robert Merritt something of a find. A gay street kid with long hair and very little “hold-back,” he could be relied upon to help Shoffler and his colleagues “infiltrate, expose, disrupt and discredit” dissident groups and their leaders. That was the mandate of secret government undertakings to which Shoffler and his cohort were a party – illegal operations like the COINTEL program and the CIA’s Operation CHAOS. In Washington, the Institute for Policy Studies was subjected to surveillance, infiltration, and disruption. So were the Red House Bookstore and underground newspapers like the The Quicksilver Times. Even the restrooms – especially the restrooms – came under surveillance. At least the ones at Dupont Circle did.

Some of this was business as usual. Washington’s gay community had been of special interest to the police and the feds since the Second World War. For more than 20 years, the Washington Police Department’s Lt. Roy Blick compiled thousands of dossiers on the city’s “perverts.” Testifying before a Senate subcommittee in 1950, “Blick described parties raided, officials high and low arrested, and ended with a real shocker,” Newsweek reported. “’There are some 5,000 homosexuals in the District of Columbia,’ he testified, ‘and 3,750 of them work for the government.’”

Of particular interest were people of influence – wayward lawyers and politicians, judges and businessmen – and their families. Male and female prostitutes and their clients were also targeted, and the results shared with both the FBI and the Security Research Staff at the CIA. That the dossiers were sometimes put to political use is undeniable, their compilation justified on the grounds that homosexuals were a national security threat.

Shoffler became Blick’s protege during the 1960s – and soon was known within the Department as “Little Blick.” He seems to have “inherited” many of his namesake’s files when the latter retired and, like Blick, liaised regularly with his FBI and CIA counterparts.

And not just his counterparts. If we can believe Merritt, Shoffler was also in touch with White House counsel John Dean.

This will give Watergate aficionados pause. There are those of us who believe that Dean unilaterally ordered the Watergate break-in. If then, it should turn out that in the weeks and months leading up to the break-in, Dean was meeting with the police officer who would eventually make the Watergate arrests, we will have arrived at an interesting and previously unknown intersectiion in the affair.

That said, it must be noted Merritt’s recollection of the supposed Shoffler-Dean meeting(s) is not in his book. It’s a story he recounted on a radio program while attempting to publicize that book. As Merritt tells it, he accompanied Shoffler to a soiree at the Old Stein restaurant in April, 1972. This was two months before the Watergate break-ins and, according to Merritt, those in attendance included John Dean and a temblor of “military brass.” Elsewhere, Merritt claims that he first met Dean before an antiwar demonstration in the capital. He’d met up with Shoffler who was on his way to a meeting with a man the detective would only identify as “J.D.” An antiwar demonstration was in the offing, and J.D. – whom Merritt later recognized as John Dean - was seated in a parked car near Dupont Circle. Merritt says he didn’t give the introduction much thought, until recently.

Why Shoffler would have brought Merritt to a kaffee-klatch of high-ranking military officers is unclear, and seems unlikely. Still, it is not entirely beyond the realm of possibility that Shoffler would have introduced Merritt to Dean if, in fact, Shoffler was liaising with Dean. And perhaps he was. Antiwar demonstrations were a part of Dean’s brief at the White House, and he is known to have kept track of them. It is at least possible, then, that he and Shoffler met from time to time to compare notes.

But revelations like these drive Merritt’s amenuensis, Douglas Caddy, crazy.

Merritt and Caddy were in regular contact for years about the book. Indeed, the book is Robert Merritt’s story as told to Douglas Caddy, who also added a thoughtful and interesting Prologue and Afterward. The problem Caddy now has with the book is that some of Merritt’s most significant and/or outrageous claims are nowhere to be found in it. They only came out when Merritt began to publicize the book, whereupon he did what Confidential Informants almost always do: he became an unstoppable raconteur. And in so doing, he may well have embellished the tale to make it even more interesting (though this has yet to be demonstrated).

Caddy’s interest in the affair would seem to be transparent. He worked with Howard Hunt at the Robert R. Mullen Company, a Washington-based PR firm that served, also, as a CIA cover and looked after Howard Hughes’s interests in the capital.

So it was that immediately after the Watergate arrests, Hunt contacted Caddy, urging him to represent the burglars at their arraignment. Because Caddy’s new clients were mystery-men with fake IDs and refused to answer questions, the curiosity of the U.S. Attorney’s office, the FBI and the cops was piqued.

And so the court brought pressure upon Caddy himself.

Subpoena’d to appear before a grand jury, Caddy at first refused to answer questions about how he had come to be involved in the case, invoking the attorney-client privilege. Judge John Sirica promptly cited the lawyer for contempt. Confronted with jail-time, Caddy relented, which meant that he was forced to testify as a witness against his own clients.

To Caddy’s way of thinking, this was not necessarily a bad thing. Sirica’s order was so outrageous that if Caddy’s clients should be convicted, the case would likely be overturned on appeal. In the event, however, this analysis was mooted when the burglars were persuaded to change their pleas to Guilty, thereby obviating any revelations about the burglary or its purpose.

Merritt’s tale brings Caddy even deeper into the Watergate story. According to the Confidential Informant, officer Shoffler and his cohort lobbied him – hard - to seduce the lawyer.

This was an allegation that Merritt had made years earlier, and which I had reported upon – somewhat skeptically – in Secret Agenda. What made me skeptical was the absence of any evidence that Caddy was gay. But I was wrong. Caddy was, in fact, secretly gay and had gone to great lengths to conceal it.

So chalk one up for Merritt. He is obviously telling the truth about this, and we can only wonder about the lengths to which Shoffler and his associates would go. And had gone. That he knew of Caddy’s homosexuality seems remarkable until we recall that Shoffler was known as “Little Blick,” and liaised with what Jack Anderson called “the CIA’s Sex Squad,” as well as basement operations at the FBI and NYPD Intelligence.

Caddy’s name no doubt appeared in one or more the “pervert files” that were available to him.

But the story doesn’t end there. In Watergate Exposed, Merritt tells us that it wasn’t just Caddy’s seduction that was sought. Shoffler and his cohort – a casserole of fellow cops, FBI agents and Pentagon spooks – actually wanted him to kill the lawyer, and offered him $10,000 – later raised to $100,000 – to carry out “the assignment.” Merritt says he refused. Apparently on…well, ethical grounds.

Let us pause.

Inasmuch as Robert Merritt’s ethical standards can only be described as “chthonic,” I find it incredible that he would turn down so much money – to do anything. Even so, I am not sure that he’s lying in every direction. Because what stands out about Merritt almost as much as his corruption is his naivete and immense desire to please. It was these characteristics that made him so easily manipulated by his police handlers. And we see it at work here, in the Caddy story, when Merritt attempts to explain the motivations of Shoffler and the Pentagon spooks. It’s a mixed bag. They certainly wanted to know how Caddy had come to represent the burglars. But according to Merritt, there were other reasons, as well. The spooks were homophobic and were happy to kill Caddy…because he was a fag. And there were political reasons, also. Caddy “knew too much about the CIA,” Merritt tells us. He was “a communist…pro-Cuban and…” – wait for it – “a leader of the Young Americans for Freedom.”

What?

As improbable story must seem, I am sure that something like it actually occurred. What makes me think so is a further detail that Merritt provides. “The exact description of the assignment,” he writes, is that “I was suppose to insert…(a) gelatin-like suppository into his rectum, which would have caused (Caddy’s) death within minutes.”

Yikes! Death by suppository! Poetic justice, no doubt, in the eyes of rightwing homophobes and yet…these are supposed to be serious people, the kinds of people who, when committing murder, place greater emphasis on efficiency than wit. Instead, what we have is what sounds a bit like the macho b.s. that one sometimes hears in locker-rooms and bars with sticky floors.

So the question presents itself: am I overestimating the intelligence of Shoffler and his cohort, or am I underestimating the intelligence of Merritt?

There can be no certainty on this point, but some of Merritt’s other “revelations”

may help us to decide. For instance, one of his many bombshells is the assertion that he tipped off Shoffler to what turned out to be the the final Watergate break-in. He did this, we’re told, on June 1, 1972.

That Shoffler may have been tipped off is something I have long suspected. I wrote about the possibility in Secret Agenda, noting that Shoffler and his buddies were waiting in an unmarked car outside the Watergate office building when the break-in took place. I was 1:30 in the morning, and Shoffler had been off-duty for hours. But this was by no means the only reason to suspect that the burglars walked into a trap. Even if we leave aside the peculiar behavior of the burglary team’s leader, James McCord – about which I have written elsewhere – there is the testimony of Capt. Edmund Chung.

He was Shoffler’s commanding officer at Vint Hill Farm. And according to Chung, who volunteered his testimony to the Senate, he had occasion to dine with Shoffler after the Watergate arrests. The burglary was front-page news, and Chung asked Shoffler how he had made the arrests. The police detective replied that he’d been in contact with Alfred Baldwin prior to the last break-in. (Baldwin was the former FBI agent hired by McCord to eavesdrop on telephone conversations that McCord claimed were emanating from the DNC.)

Shoffler’s implication, then, is that it was Baldwin who had tipped him off. (Baldwin acknowledges having met Shoffler at an antiwar demonstration.) If the whole story ever came out, Chung says Shoffler told him, “his life wouldn’t be worth a nickel.”

There is no mention of Chung in Merritt’s book, and the men’s stories are by no means of a piece. While they are in agreement that Shoffler was given advance warning of the June 17 break-in, they differ on the source. According to Merritt, it was he – and not Alfred Baldwin – who warned Shoffler. He says he did this on June 1, after being told of the impending break-in by a switchboard operator at the nearby Columbia Plaza Apartments. “She,” we are told, had learned of the break-in plan while eavesdropping on a telephone conversation between two men.

Merritt’s account of the incident is detailed. The switchboard operator is said to have been “a drag-queen” named James Reed, a/k/a “Rita.” The telephone connection apparently consisted of a so-called “reserve line” – one of three on the switchboard – that did not connect to the apartments. Asked about this, a former supplier of bugging equipment to the FBI suggested that the line in question may have been in use by an eavesdropping operation in the basement or elsewhere in the apartment complex.

The problems with (this part of) Merritt’s tale are several, and fundamental. For instance, the first successful burglary of the DNC occurred on the night of May 28th, 1972. A handwritten log, summarizing telephone conversations that Baldwin overheard from his listening-post in the Howard Johnson’s Motel, was edited by McCord and given to Gordon Liddy two days later. In other words, Liddy received the logs on June 1 – the same day Merritt says he told Shoffler about a break-in that was set for June 18th.

The problem, of course, is that there was no perceived need for a second entry at this time.

It was not until a week later – on Friday, June 9th – that the Committee to Re-Elect the President’s Jeb Magruder pronounced the eavesdropping logs “worthless.” Coincidentally, this was the same day that a front-page story appeared in the The Washington Star, linking the White House to a “Capitol Hill call-girl ring” with ties to the Nixon White House. John Dean reacted to the news with alacrity, if not panic. Grabbing the phone, he summoned the Asst. U.S. Attorney who was handling the case to come to the White House – and ordered him to bring “all the evidence” with him.

The weekend intervened, and it was not until Monday, June 12th, that Dean’s subordinate, Jeb Magruder, told Liddy that there would have to be a second entry to the Watergate.

This sequence of events is a well-established part of the Watergate narrative. On its face, it would seem to rule out a June 1 plan to re-enter the DNC more than two weeks later.

But maybe not. When Douglas Caddy is asked about this, he acknowledges the problem and suggests a solution. Perhaps, he says, Magruder and/or Dean were taking orders from a person or group outside the White House and the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CRP). Like who? Like what? The Pentagon, Caddy suggests. Or the CIA.

There is no evidence that this is what occurred, though it would tend to explain a second problem that is fundamental to Merritt’s account.

According to Merritt, his source (James “Rita” Reed) told him that the break-in would destroy the Nixon Administration. Which, in a sense, it did. But this could not have been foreseen as a consequence of the burglary itself. The Administration was actually destroyed by a perfect storm that included the relentlessness of the liberal media; the influence of the Kennedy machine upon the Senate Judiciary Committee; the slow-motion hemorrhage of the Administration’s secrets, crimes and improprieties; the destructive duet of James McCord and John Dean; and, not least, the Administration’s clumsy attempts at a cover-up.

Until those events had come to pass, the Watergate incident was little more than a serious embarrassment – one that Nixon appeared to have overcome through his re-election. To claim, as Merritt does, that Nixon’s downfall was foreseen in early June suggests either supernatural clairvoyance or a conspiracy of Byzantine proportions.

In the event, neither Caddy nor Merritt see this as an obstacle to the latter’s credibility. On the contrary, they imagine the unfolding of a “Seven Days in May” scenario – in other words, they believe “Watergate” was a coup d’etat.

As evidence of the conspiracy, Merritt offers yet another revelation that is not in his book, but which he recounted (much to Caddy’s chagrin) after the book was published.

According to the police informant, Shoffler and a team of Pentagon spooks drugged and kidnapped the CIA’s special counsel, Mitch Rogovin, in 1975. Though Nixon had resigned by then, the Church and Pike committees were investigating (respectively) CIA abuses and the Agency’s involvement in the Watergate affair.

According to Merritt, the Pentagon feared that an in-house CIA report (marked “Eyes Only,” “Secret,” and/or “Confidential”) would reveal the existence of a military spying operation targeted at the former Nixon White House. The purpose of the Pentagon operation, we are told, was to bring down the Administration.

The 400-page CIA report was supposedly entitled Confidential Report on Intelligence of Military Secret Operations on Nixon. By way of clarification, the report was said to be subtitled Report of Operations of Secret Surveillance and Eavesdropping. Perhaps to facilitate discussion, the putative report was conveniently referred to by its acronym, C.R.I.M.S.O.N R.O.S.E. (though C.R.I.M.S.O.N R.O.S.S.E. would have been more accurate).

I must confess that I am not sure where to begin with this, as we seem to have arrived at a S.I.L.L.Y. P.L.A.C.E. The most obvious point to make, I suppose, is that if Merritt is telling the truth, the CIA is in desperate need of a copy editor. “Secret Surveillance and Eavesdropping”? Sounds a bit like “wet water,” does it not? As for the report’s classification, it is the first that I have ever seen to have been designated “Secret,” “Confidential” and “Eyes Only” – all at once.

No matter. Shoffler and his alleged team of Pentagon spies were determined to obtain the supposed report – though it is by no means clear what they intended to do with it. In the event, we’re told they lured CIA lawyer Mitch Rogovin to the Mayflower Hotel, spiked his drink with knock-out drops, and dragged him to the hotel’s freight elevator – which Merritt claims he was operating. Carried to a room, the hapless and unconscious attorney was stripped to his wedding ring and placed in embarrassing postures with a whore.

The purpose of the exercise, we’re told, was to persuade Rogovin to retrieve the Crimson Rose report, which had been sequestered in a Secure Room at CIA headquarters in Langley. There, it was chained to a table in a large binder. Fearful that the photos might be leaked, Rogovin supposedly retrieved the Crimson Rose report and gave it – with the severed chains till dangling from the binder – to Shoffler and his team of Pentagon spooks.

Seems unlikely, does it not? Even if Pentagon’s spies were so deranged as to mount an operation as crude and egregious as the one that Merritt describes, what did they hope to do with the report? Would it not have occurred to them that there might be a copy? Moreover, what was to be done about Rogovin? The Secure Rooms that Merritt refers to are guarded by Marines and/or CIA Security staff. A record is maintained of all who enter and leave them, and closed circuit television cameras record the comings and goings of all visitors. Leaving aside the question of Rogovin being subject (as all CIA employees are) to regular polygraph testing, surely someone might would have noticed a dangling chain and missing binder in the Secure Room.

With the Crimson Rose story, Robert Merritt descends to opera bouffe. The Pentagon spy-ring that he has christened “Crimson Rose” is obviously derived from the Moorer-Radford incident, in which a Navy yeoman rifled Henry Kissinger’s briefcase and burn-bags. The secrets he obtained were dutifully conveyed to Adm. Thomas Moorer, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff – though it’s unlikely that any of it was news to him. Washington Post reporter Jack Anderson, a friend and co-religionist of Yeoman Charles Radford, may also (and especially) have been a consumer of the looted materials.

The Moorer-Radford incident is, of course, anything but news. It is discussed in Secret Agenda and other books and news articles. The Pentagon and White House investigated the affair, which the Pentagon’s own chief investigator (Donald Stewart) compared to a “Seven Days in May” scenario. If there was a secret report on the Moorer-Radford affair, it was therefore more likely to be held in a Secure Room at the Pentagon (and/or the White House) than at the CIA.

In this connection, it is at least ironic to note that Yeoman Radford’s espionage was, if anything, trivial compared to the CIA’s own surveillance of the Nixon White House. It is a fact that all of the photos taken and all of the documents stolen by the Plumbers were diverted to the CIA – with the White House receiving either nothing at all, or adulterated versions of the take.

***

Finally, what may be said about Robert Merritt is that he is, by profession, a lifelong snitch and provocateur who admits to having “committed so many crimes at the direction of the FBI that had I been indicted, the list of felony counts would have set a world record and, if convicted, I could have received one of the longest sentences in history.”

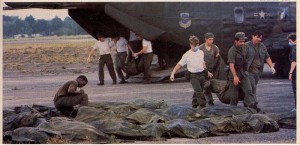

According to Caddy, Merritt’s activities included “lying to…two comittees of Congress and a Special Prosecutor; participating in the theft of a Top Secret…national security document obtained through kidnapping, blackmailing and extorting the General Counsel of the CIA; (and) distributing candy containing poison to anti-war demonstrators and later claiming over a hundred of these persons died as a result.”

To these sins, we may add that Merritt also admits to having whored for the police and the Feds, by going after liberal political targets such as Sen. William Proximire.

Merritt is, in other words, a “man for all seasons,” albeit a gay one. His bottom-line is that, like all snitches, he needs a patron or a client – someone who will immunize him from own misdeeds, so long as he returns with whatever is needed (whether what’s needed is there or not).

That said, at this late date, it is doubtful that even Merritt knows what’s true or false about his past. So desperate does he seem for validation – money or fame, infamy or redemption – he will, I think, “remember” whatever it takes to rescue himself from a clear view of his own life.

William Burroughs called it “the naked lunch,” and Merritt has been dining on it for quite awhile. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t listen to him. While reserving judgment on Merritt’s bona fides, journalist Phil Stanford notes that some of Merritt’s more interesting and controversial claims would seem to be corroborated elsewhere. Even so, to rely on Merritt as a source would be folly. Best, then, to treat his information as leads and seek verification where it can be found.

As for Douglas Caddy, his contribution to the Merritt story is an important one. His Prologue, Afterword and letter to FBI Director Mueller contain new revelations about Watergate and the COINTEL program, while raising any number of interesting questions. For instance, we can only wonder why an experienced spook such as Howard Hunt would have turned to Caddy to represent the burglars at their arraignment. Both Caddy and Hunt were employed by the Robert R. Mullen Company, which the CIA used as a cover – a cover that the Agency was desperate to protect. Dragging Caddy into the Watergate affair could only have served to expose that cover (as, indeed, it did). From a tradecraft point of view, this was madness and we can only wonder about Hunt’s inentions.

From a tradecraft point of view, this was madness – unless Hunt hoped that the CIA would intervene with cries of “National security!” and shut the investigation down.

Caddy is interesting, as well, for having been recruited at this time to build and run a luxury hotel in Nicaragua for the CIA. The Agency, he was told, hoped that the hotel would attract Sandinista rebels to its gaming tables. I emphasize “he was told” because the rebels were not exactly what Vegas would consider “a pod of whales.” What seems more likely is that the putative hotel would have been used as a secret hospice for the CIA- (and Robert R. Mullen-) connected billionaire Howard Hughes. In the end, the Agency’s offer to make Caddy a hotelier proved to be a non-starter. The lawyer declined the post, knowing that a mandatory CIA polygraph would “out” him.

If nothing else comes out of Merritt’s tome, the book will have been worth it for those bits alone.

-30-