Since this was written, President Clinton has pardoned Marc Rich and Pinky Green, the Russian economy has taken off, and one of Rich’s own lawyers—Vice President Cheney’s former chief-of-staff, Lewis “Scooter” Libby—is himself a defendant in the criminal courts. (This, in connection with the Valerie Plame imbroglio.) What’s to be made of it all? I’m not sure. But other than Richard Nixon, I can think of no other felon, or quasi-felon, who has been pardoned for his crimes without having first been convicted of them. Perhaps the explanation is that Rich and Green have been helping their countries – the United States and Israel – behind the scenes. Like Hollywood tycoon Arnan Milchan, who is widely alleged to have long used his businesses to help finance the operations of the Mossad, former 20th Century Fox honcho Rich may well have done the same…if not for the Mossad, then perhaps for the CIA.

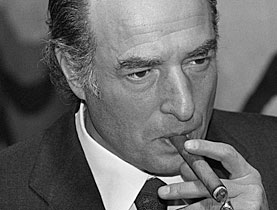

Light snow falls through the darkness as a gray Mercedes glides out of the driveway of one of the oldest and most spectacular mansions in Switzerland.

As the car winds its way into the mountains above the lake, windshield wipers brushing at the snow, a man in a black cashmere coat and a dark blue suit sits in a cone of light in the backseat, reading. Not far behind, a chase car flirts with the Mercedes’ rear bumper, surging closer and closer, then falls back. Inside, three Israeli bodyguards scan the road, alert for the possibility of a bounty hunter’s ambush or a terrorist’s kidnapping.

The man in the Mercedes is at once honored and infamous. There is a fellowship at Oxford University in his name, and his foundation disburses millions to worthy causes. Despite this, indeed, despite all the good he’s done, he remains a fugitive, wanted by the FBI, Customs, the IRS, U.S. Marshals and Interpol. Should he be caught and convicted, he could face more than 300 years In prison.

It would be helpful, then, to know what he is reading as he leans back in the leather seat, engulfed by darkness, luxury and paranoia. At five A.M. it is too early for the newspapers; they’ll be waiting on his desk when he arrives at the blue glass cube that is his office building. But there are the late-night faxes, certainly, and it may well be that among them is a message from one of his lawyers – the best that money can buy. It could be a note from Leonard Garment, then, or Brad Reynolds or perhaps not.

Perhaps it’s a message from his bustling Moscow office, or a copy of the most recent missive from the secret police of the mineral-rich republic of Kazakhstan. For nearly a year, renegade Kazakh spooks have been quietly distributing diatribes against him to the press, accusing him of a host of crimes in an effort to discredit his company and sabotage his business.

And in Moscow itself, ultranationalist newspapers have published articles alleging that his commodities business is a front for laundering drug money. He denies the allegation, but it has its believers. His companies have an annual turnover of more than $3 billion per year in what was formerly the Soviet Union, so the man in the Mercedes bestrides the disintegrating Russian economy like a sumo wrestler on a pony.

Considering the stakes, it is hardly surprising that business rivals would stoop to slander in an effort to knock him off. Then again, he may be studying the numbers. As in: How many tons of aluminum are stored in his Rotterdam and Singapore warehouses? How many board feet of timber were taken from his forests in Chile last month? How many tons of light crude petroleum are moving across the oceans in his tankers?

A Belgian-born American with Spanish and Israeli citizenship (and a pending application to Switzerland), the man in the Mercedes is Marc Rich, a billionaire over and over again, and one of only a handful of people who might reasonably be called, in novelist Tom Wolfe’s parlance, a “master of the universe.” Unlike Wall Street wheeler-dealers who trade in the abstractions of futures contracts, stocks and bonds, Rich is a player on the periodic table itself, buying and selling strategic quantities of the world’s raw materials – its very elements – as well as more complex compounds (sugar, soybeans, oil, government officials). He is a titan in the business of wholesaling the planet’s natural resources to the highest bidders.

He owns or controls oil wells in Russia, mines in Peru and electrical supplies in England. There are refineries in Romania, office buildings in Spain and smelters in Australia, Iran, Sardinia and West Virginia. He has 40 offices and 1300 employees throughout the world and is simultaneously the uncontested emperor of aluminum, a prince of sugar, a shogun of soy, a mover and shaker of the world’s markets in nickel, lead, zinc, tin, chrome, magnesium, copper and coal.

One could go on. The managing director of a private intelligence network in the U.K., one that has followed Rich for more than a decade on behalf of a secretive Arab client, says bluntly, “Marc owns Peru,” and this isn’t so hard to believe. With an annual turnover in excess of $30 billion, Marc Rich & Co. AG has a larger turnover than the GNPs of many Third World countries-including the two dozen whose economies are said to be entirely within his hands.

Sitting in the back of his Mercedes, it may be that he is reading Izvestia, faxed from the Moscow office. He would agree that the Russian newspaper has behaved responsibly in the past, defending him against the U.S. Justice Department in a front-page editorial. But now, in the new Russia, the newspaper has actually opened its pages to investigative reporters and other idiots. Only recently, Izvestia reported that a $750,000 reward had been offered by the U.S. for Rich’s capture, while suggesting that he was somehow responsible for the export from Russia of 700,000 tons of high-quality fuel oil, purchased for a fraction of its cost. (His profit was estimated to be between $48 million and $400 million.)

There are other allegations, of course, and a blizzard of rumors. It is said by one of his competitors, for example, that Rich has corrupted executives at the Finnish national oil company and that he’s using them to plunder their country’s economy.

Trade unionists in Romania accuse Rich of having banked the fortune that Nicolae Ceausescu stole, and a freelance spook in what was formerly Ollie North’s apparat insists that Rich worked hand-in-glove with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union to loot the U.S.S.R. of its gold reserves during the Eighties. The Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Terrorism, Narcotics and International Relations has called for an investigation of Rich’s connections to the infamous and now defunct BCCI.

And so it goes. In Amsterdam, the anti-apartheid Shipping Research Bureau accuses Rich of busting UN sanctions against South Africa. In New York, the authoritative Platt’s Oilgram News reports that he made oil shipments into Serbia at the same time the UN was preparing a blockade against that bellicose country. In London, Private Eye suggests the billionaire has been trying to violate similar embargoes imposed by the UN against Iraq.

But what do they know? Can anyone really be all that bad? (Can anyone really be all that rich?)

The rumors fall like snow past the windows of the Mercedes. But Marc Rich isn’t reading rumors. He knows the truth, and if he doesn’t, he can pay to have it found. Perhaps, for instance, he’s reading the report that he commissioned on a question of some delicacy – the report on the provenance of his blonde German girlfriend. Avner Azulay, an Israeli private eye, was hired by Rich to find out (among other things) if the woman’s family was pro-Nazi during the war. The detective’s report brought welcome news.

And so the man in the Mercedes can relax. It’s almost dawn in the Alps, he hasn’t been snatched and his girlfriend is clean. What more could a man want?

What more, indeed?

To understand who Marc Rich is, we need to know how one of the most powerful men in the world came to be a prisoner in paradise and a capitalist in flight.

Let us, then, begin at the beginning: Marc Rich (nee Reich) was born in Antwerp in 1934. He came to the U.S. with his parents eight years later, arriving in 1942. With the war in Europe behind them, the family settled in Kansas City, Missouri, where Rich’s father opened the Petty Gem Shop and earned a modest income. Rich attended public schools (where he seems to have made no impression whatsoever on his classmates), joined the Boy Scouts and went to summer camp in the Ozarks. (One of his tent-mates was writer Calvin Trillin, who remembers Marc as “the quietest kid at Camp Osceola. “)

To have been a Jew in Kansas City in the Forties (and one, moreover, who spoke three languages while still a child) could not have been easy. But he didn’t live there for long. The Petty Gem Shop prospered and became the diversified Rich Merchandising Co., which Rich’s father soon sold at a nice profit. In 1950 the family moved to New York, where the elder Rich entered into a partnership to manufacture burlap bags. With the Korean War shifting into overdrive, this proved to be a brilliant stroke: Military requirements pushed the demand for burlap through the roof, and the family’s fortune was made.

By then, Marc was enrolled at New York University. But as a sophomore, he was lured away from school by an acquaintance of his father’s, who wanted him to apprentice as a commodities trader at Philipp Brothers.

In 1954 Philipp Brothers was the biggest raw-materials trading company in the world, bridging the gap between mining and manufacturing companies on five continents. Established by scrap-metal merchants in Hamburg during the 1890s, the firm had expanded to England and the U.S. in the years before World War One. By World War Two it had become a giant with enormous influence in the Third World.

Rich began to learn the metals-handling business while working in the traffic department at Philipp Brothers. Like many of the other apprentices, he was the son of Jewish refugees. Unlike them, he’d grown up in the Midwest, surrounded by goyim. His father was a millionaire who was well-connected at Philipp Brothers itself. Marc wore suits that the others couldn’t afford, and he came to work in a red MG TD that seemed to instill envy in all who saw it.

Four years after leaving NYU, Rich was given his first assignment abroad. Sent to Havana on the eve of the Cuban revolution, he found himself in a vortex of decadence and corruption. It was a place where almost nothing worked except the bribe, which always worked. Rich got the company’s metal out of Cuba and was sent out into the world to make even more money for Philipp Brothers. He began to travel constantly between New York and La Paz, Cape Town and Santiago, taking time out to get married in 1966. His wife is the almond-eyed Denise Eisenberg, a New Englander who, like her husband, was the child of Jewish refugees who’d made a fortune in America after the war.

Unlike Marc, however, Denise was a rock-and-roller. He lived in a world of boardrooms dominated by patriarchal millionaires; she was a junk-food addict who loved the movies and was as driven to make it as a pop star as her husband would one day be driven to corner the world’s free-aluminum market.

Within a year of marrying, Rich was placed in charge of the Philipp Brothers’ office in Madrid and given a seat on the company’s European management committee. Always an insider, he was now privy to many of the company’s most closely held secrets, overseeing virtually every trade that Philipp Brothers made on the continent. Not content with that, he pulled off an extraordinary feat: in the late Sixties he invented the spot market for oil.

After World War Two, the world market was dominated by the Seven Sisters–companies that controlled the price and production of oil from wellhead to gas pump. By tapping suppliers in countries that had more oil than scruples – Iran was such a place – Rich and his Philipp Brothers’ associate, Pincus “Pinky” Green, were able to buy excess crude and sell it to refineries operating at less than capacity. In this way, the Seven Sisters were bypassed, and a gusher was tapped.

In the spring of 1973, Rich and Green anticipated the huge price increases that the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries would impose in the autumn. Acting on tips, possibly from sources in Israel, OPEC or the State Department, they learned that the price of oil on the spot market would jump (in fact, it would triple). So they bought $150 million worth of crude that spring, paying $5 a barrel above the spot price to get it.

It was a great deal, but a mixed blessing. The reaction at Philipp Brothers was unmitigated terror. Rich was forced to sell the oil before the embargo took place. In effect, the directors of Philipp Brothers cashed out before the winning hand was played. Belatedly, they realized their mistake and gave Rich and Green a freer rein. The resulting profits were enormous. And so were the bonuses owed to the two traders.

Indeed, the bonuses were so large—as unprecedented in their size as the oil deal had been risky—that the company refused to pay. So Rich and Green bolted, taking with them a half dozen of the firm’s best traders. In 1974, armed with pledges of as much Iranian oil as they could handle, the unlikely pair began trading as Marc Rich & Co. AG.

From the beginning they waged a private war against Philipp Brothers, doing everything in their power to destroy the company. Secretaries and clerks were bribed to provide copies of the opposition’s telexes, which enabled Rich and his cohorts to win contracts by bidding only pennies more than Philipp Brothers for tons of metals and grains. There were even allegations that Rich’s operatives had bugged the company’s headquarters in New York.

By the early Eighties, Phibro-Salomon (Philipp’s name after a merger with Salomon Brothers) was reeling, and Marc Rich and Co. had an annual turnover in excess of $10 billion. And yet, even while operated as a kind of pawnshop for the mineral wealth of the Third World, Marc Rich & Co. remained an enigma. Which was exactly the way Marc Rich wanted it.

To many, Rich’s obsession with secrecy bordered on paranoia, but the reality was that secrecy and profits were intimately linked. To pull off his deals, Rich often had to rely on bribery and sanctions busting. Throughout the Seventies and Eighties, for instance, South Africa was subject to oil embargoes imposed by the United Nations, OPEC and the European Community in response to that country’s apartheid policy. For a commodities trader like Rich, headquartered in neutral Switzerland, the UN embargo was made to order. The Afrikaners were happy to pay more than $8 a barrel over spot, which meant profits of more than $100 million on each contract Rich’s company brokered.

Nor was it particularly difficult to find a supplier. The Soviet Union needed hard currency to buy grain and build submarines, and one way to get it was by ignoring its own trading sanctions against an oil-thirsty country such as South Africa. With the buyer and seller lined up, all that was necessary was to launder the oil through a purposefully convoluted series of corporations chartered in such venues as Monaco, Liechtenstein and the Cayman Islands. Sometimes, when the cargo was delivered, the tanker would be scuttled and the seamen sent home by air. Subsequent investigations would reveal that the missing ship’s owners were headquartered at a Swiss post-office box—on which the monthly fee was overdue.

One such shipment left the Black Sea in September 1988, sailing aboard the Dagli, a Liberian oil tanker flying a Norwegian flag, carrying Soviet oil bought by a Greek firm for delivery to Italy. The muddled itinerary and ownership made tracing the vessel next to impossible. Slipping through the Dardanelles, the ship kept on going as it passed Sicily, and continued on through the the Straits of Gibraltar. Turning left at Tangier, it began communicating in code and covered its name in tarpaulins. The oil was eventually delivered to Cape Town in mid-October. According to Amsterdam’s Shipping Research Bureau, which investigated violations of oil embargoes against South Africa, “the whole masquerade had been set up by the real buyer, Marc Rich, who made use of a company that soon after ceased operating and another company belonging to his empire of which no traces are left at all.”

Experts estimate that Marc Rich supplied at least eight percent of South Africa’s oil needs during the Eighties, arranging for more than 75 secret shipments from the Soviet Union, the Persian Gulf and Brunei. The value of those shipments was in the billions, and so were the profits. But that was only a part of Rich’s payoff. When Phibro-Salomon stopped trading with South Africa in 1985, responding to anti-apartheid activists in the U.S., Rich quickly stepped in to fill the gap, replacing the firm as the exclusive sales agent for one of South Africa’s largest lead mines.

The South African trade put Rich into the sanctions-busting business in a big way. Rich must have convinced himself that political sanctions did not apply to his operations, or, if they did, that clever lawyers could get around them.

It’s not surprising, then, that the 1980 U.S. embargo against Iran was viewed by Rich as an opportunity to make a killing. Laundering Iranian oil through Panamanian fronts and sham transactions, Rich’s company was able to subvert price controls, evade taxes and move hundreds of millions of dollars in illicit profits offshore. Unfortunately for Rich, however, the deals also brought an indictment.

A pair of Texas oilmen, who were themselves under indictment for falsifying the offshore origin of what was purported to be domestic oil, offered up Marc and Pinky in return for light sentences. Rich and his partner were each charged with 51 counts of conspiracy, tax evasion, racketeering and trading with the enemy. Anticipating the indictment, Rich locked the doors to his ten-room apartment on Park Avenue and fled New York in early June 1983. A few days later, he and Denise were ensconced in Switzerland in a mansion overlooking the town of Zug. The indictment came down a few months later.

Although Rich and Green each faced more than 300 years in prison, they knew they’d be safe in the Alps. The extradition treaty between Washington and Bern was so old that it predated the income tax itself. It covered murder, rape and mayhem, but, the Swiss maintained, nothing in it applied to “the modern crimes” for which Rich and Green had been accused. In essence, since neither had strangled anyone, the billionaires were more than welcome to remain in Switzerland.

Meanwhile, and at a cost of more than $10 million, a platoon of brand-name lawyers (Edward Bennett Williams, Michael Tigar, Boris Kostelanetz and others) was deployed to wage a rearguard battle in the States. There, the courts had blocked some $50 million in payments owed to the Marc Rich group by other companies, and the prospect of property seizures seemed likely. There was, in addition, a contempt-of-court fine that amounted to $50,000 a day for Rich’s refusal to surrender subpoenaed documents to the U.S. Attorney’s office.

Rich paid the fine by check in twice-weekly installments, complaining from Switzerland that if he surrendered the documents, he would be guilty of business espionage under Swiss law. This view was echoed by the cantonal prosecutor in Zug—though, admittedly, he sat on the boards of more than 30 of Rich’s corporations and so might not have been entirely objective.

Even as the legal battles continued, Rich knew that one could do worse than to be rich in Zug. With its fiscal pheromones of low taxes, bank secrecy and lax incorporation requirements, Zug was a mecca for businesses that operate on the edge.

And Marc Rich was in the middle of it. His mansion overlooking the Zugersee was decorated with Picassos, a Miro and a Braque. He skied at St. Moritz, where he maintained a luxurious chalet, and began to host a New Year’s Eve party for tout l’Europe. Placido Domingo was a guest, as were a constellation of other celebrities. Rich attended charity balls in Geneva and Lucerne, where he gave generously to the fight against fashionable diseases, and he caused a stir at the World Economic Forum in Davos.

Taking a page from the extraditables in Colombia, he bought the approval of the little guy in Zug by pouring money into the local sports franchise, dramatically improving the fortunes of the Zug hockey team (now one of Switzerland’s best). Nor were his philanthropies confined to Switzerland. When the Jamaicans began to complain about Rich’s hammerlock on their aluminum industry, the fugitive billionaire responded by underwriting the costs of the country’s bobsled team at the 1988 Olympics.

Denise Rich, meanwhile, was making it big on her own. In 1985, a Sister Sledge rendition of one of her songs, Frankie, topped the British charts for six weeks, selling more than 750,000 copies. Denise followed Frankie’s success with her own album, Sweet Pain of Love, which may or may not have been inspired by her husband’s pursuit of beautiful aristocrats. In any event, the fugitive was now married to a rock star who appeared on European TV.

In the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge, in a washed-out office with cipher locks on the door and a metal detector at the entrance downstairs, a federal marshal plotted to bust Marc Rich. Indeed, Rich and Pinky Green were the sum of his caseload, and they occupied every hour of his day. The marshal spoke regularly with Rich’s rivals, with would-be bounty hunters, disaffected employees and customs officials and cops in the most remote corners of the world. He knew who Rich slept with, where he had dinner and how much he drank. From time to time he packed a valise and went after the fugitives, but the operations he mounted were never successful.

Learning that Rich was en route by private jet to Helsinki, he arranged for the plane to be met by police. Incredibly, Rich’s flight made a U-turn at 20,000 feet and headed back to Switzerland. A more ingenious plan required the cooperation of the Jeppesen Sanderson company, which has a near monopoly on the sale of aeronautical charts. Knowing that Rich’s widespread business interests required him to fly to some of the world’s most remote places, the marshal asked the company to tip him off whenever Rich’s pilots requested new charts. Jeppesen Sanderson refused to help. And so it went: The marshal couldn’t get the cooperation he needed, and whenever a trap was laid, Rich eluded it. Clearly, Rich had better spies than the U.S. Marshals Service could muster.

A lesser man might have been content to cut his losses and enjoy his millions in the Alps. But not Marc Rich. Although his companies had been indicted on an array of serious charges, and he himself was reduced to the status of fugitive racketeer, Rich still wanted to do business in America. All he needed was someone to front for him until his lawyers could reach a settlement with the Justice Department.

The line between chutzpah and hubris is a thin one, and Rich crossed it when he sent a trader named Bob Tribbett to New York in May 1984, instructing him to arrange a soybean transaction with Romania. It wasn’t a big deal by Rich’s standards, only $24.5 million, but it was obviously important to him because, in the end, it cost him millions and taught him a dangerous lesson: Fugitives are fair game.

To complete the deal Rich proposed, Tribbett hired Robert Whitehead, an investment banker, unaware that Whitehead was hooked up with the FBI and the DEA, for whom he was a contract informant. Whitehead’s office suite, telephones, car and private plane were bugged.

None of this was known to Rich or Tribbett, who had other things on their minds, not the least of which was an unusually sensitive transaction with Iran.

Four years earlier, when the American government left Iran to the Ayatollah Khomeini and the mullahs, U.S. military attaches and advisors sabotaged computerized records and equipment, including anti-aircraft missiles, the guidance systems of which were removed by departing American advisors.

Enter Marc Rich.

According to Whitehead, Rich used his contacts to obtain gas-fired gyroscopes from North Korea, providing them to the Iranians as replacements for the missing guidance systems. Suddenly, at a crucial point in the Iran-Iraq war, Iranian missiles became a factor. It was as if Marc Rich had delivered an entire inventory of missiles to the ayatollah’s forces – long before Irangate. (It would be a year before Iranian, Israeli and U.S. negotiators would meet in Europe for the first time to discuss swapping Hawk missles for U.S. hostages in Lebanon.) What Rich got in return for the gyroscopes is unknown, but putting the ayatollah in his debt could not have hurt his position as one of the world’s largest independent oil brokers.

Meanwhile, even as the gyroscope deal went down with Iran, Whitehead obtained a $24.5 million loan fom the Marine Midland Bank for the soybean transaction. Tribbett says that Whitehead was supposed to receive about $35,000 from the Marc Rich organization for his part in the deal, but Whitehead admits that he took about $5 million instead.

The FBI confirms that figure as the amount that went missing on Whitehead’s watch, though what happened to the money is unclear. Tribbett suggests that Marine Midland used the funds to cover Whitehead’s other debits at the bank. Whitehead’s FBI handler has a different explanation: “To tell you the truth, I think he just pissed it away.”

In any event, Rich found a better way to do business in the U.S. while still on the run. In the fall of 1984, lawyers for Rich and the U.S. Attorney’s office for the Southern District of New York arrived at a compromise. Marc Rich & Co. AG, and Clarendon, Ltd. (formerly Marc Rich International) pleaded guilty to dozens of criminal charges, sustaining $171 million in fines (including $21 million for contempt of court in refusing to surrender subpoenaed documents). Rich raised the money by selling a 50 percent interest in 20th Century Fox to oilman Marvin Davis, with whom he had co-owned the studio. From then on, the U.S. government had no further claim on Rich’s companies, though Rich himself remained a wanted man.

Today, Rich’s biggest play is under way in what was formerly the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc. Brimming with natural resources, “the Wild East” is a political and economic mess. A diverse group of ministries holds sway over a melange of ethnic mafias, born-again capitalists, footloose KGB agents and what used to be called “the masses.” It is a world in which billions of dollars in Soviet gold reserves have been looted by Communist Party apparatchiks, at least three of whom are reported to have cartwheeled to their deaths from the windows of Moscow office buildings.

The once vast reserves of Soviet gold have dwindled toward zero, while more than 1000 tons have been smuggled out of the country to Zurich and Tokyo aboard military cargo planes and Aeroflot flights. Under-the-table transactions by the managers of mines, along with clandestine shipments by factory supervisors, are now so frequent that border republics such as Latvia and Estonia have become major exporters of copper, nickel and aluminum–even though none of these metals is produced in either country. Meanwhile, privatization continues with all the deliberation of a national fire sale.

It is, in other words, just the sort of place in which a man like Rich can make a killing. Who’s to stop him? In 1992 the Russian government considered posing a moratorium on all business dealings with Marc Rich & Co. AG pending “a thorough investigation.” Other allegations surfaced that Rich has been illegally exporting raw materials, bribing government officials and aiding capital flight from the country.

Despite the official pronouncements against him, Rich has seen his operations in the former Soviet Union grow exponentially in the past year. Where ten employees once sufficed, 150 have now been hired, and the company’s regional turnover is in the billions. Rich and his colleagues have stepped into the void left by the shattered Communist infrastructure, taking over many of the functions once carried out by Soviet trading organs.

In this, the man in the Mercedes has been abetted almost as much by his contacts as by the vaults of currency at his command. And of those contacts, none are more colorful or well-connected in intelligence circles than an Orthodox rabbi named Ronald Greenwald.

A Brooklyn boyhood chum of Pinky Green’s, Greenwald is both a rabbi and a commodities dealer. As an agent for Marc Rich in New York, he is also one of those rare spiritual advisors who find it necessary to deny that he’s a CIA agent and/or a front for the Mossad. Affable and wry, the Reb is himself an important player in war-torn Tajikistan, where convoys of aluminum are escorted by private armies in the Reb’s employ.

Meanwhile, there are signs that Greenwald’s persistent lobbying for Rich and Green’s freedom from their pending indictments, in tandem with the efforts of Leonard Garment and former Justice Department official Brad Reynolds, is having an effect. When Representative Bob Wise (D-W. Va.) convened a subcommittee hearing two years ago on Capitol Hill, seeking to learn why the Justice Department has been unable to nab one of the most conspicuous fugitives in the world, representatives from Justice at first refused to appear before the subcommittee and then stonewalled it. Wise was outraged.

“This isn’t your average miscreant who has fled the country for knocking over 15 7-Elevens and is kicking around the dock at Marseilles;’ he said. “This is Marc Rich operating with total impunity out of a tall office building in Switzererland. Why hasn’t this been made a priority?” He noted that Rich is under indictment for trading with the enemy and for “the biggest tax fraud in history.”

Despite the seriousness of the charges, Wise said, there seems to be “a lack of political will” to apprehend Rich and Green. Wise pointed out that the government has yet to publish a reward for their arrests or, for that matter, a wanted poster. Despite the severity of their crimes, Wise noted, neither man is among the 15 most-wanted fugitives currently being sought by the U.S. Marshals Service—though several thugs who have knocked over 7-Elevens are prominent on the list.

Calling the case “strange,” the subcommittee criticized Justice for its “lack of relentlessness” and cited numerous failures in the department’s handling of the case. The worst of these may well have been its failure “to ensure that, at a minimum, the fugitives do not make money from the U.S. government.”

Until recently, Rich and his companies have continued to do business—big business—with the U.S. government, despite Rich’s status as a fugitive. The Commodity Credit Corporation has enabled the elusive billionaire to sell American grain by providing more than $50 million in export subsidies to one of Rich’s companies. As bizarre as this may seem, an even greater irony rests with the U.S.

Mint’s reliance on Marc Rich for the copper, nickel and zinc that it needs to (literally) “make money.” Between 1989 and 1992, the Rich organization sold more than $45 million in metal to the Mint.

Through the efforts of Congressmen Dan Glickman and Bob Wise, Rich is no longer doing business with the CCC or the Mint. But not much else has changed. There is no evidence that the Justice Department has acted on recommendations made by Congress.

On the contrary, the only change known to have taken place is that the hardworking marshal, who knew more about Rich and Green than perhaps anyone else in government, has been taken off the case and reassigned to Tampa.

To anyone attending the Wise hearings, the conclusion was virtually inescapable that Rich and Green are being protected—and not just by the Swiss and the Colombians.

One can speculate about the sources of Rich’s protection in the federal government. He is, after all, in an excellent position to further certain U.S. foreign policy objectives and to satisfy various intelligence requirements in Third World countries. It would hardly be surprising, then, if the State Department, CIA or National Security Council were to enlist the help of a fugitive with Rich’s broad access and enormous means.

It should be remembered, too, that Rich has a complex and intriguing relationship with the Justice Department. When Congressman Wise questioned Justice about its contacts with Rich’s attorneys and other agents, seeking to make a deal on his behalf, the department refused to discuss the matter. Why Justice should stonewall Congress on behalf of a fugitive is uncertain, though few would doubt that the wall was built to conceal the fact that Rich is working with Justice (and quite possibly with other agencies) on what can only be called “special projects.”

In the past year or so, the Justice Department has quietly inserted two sealed envelopes into Rich’s court file. While those envelopes are not to be opened unless Rich is brought before the court, there can be no doubt that the contents of at least one envelope pertain to Rich’s efforts to help the Justice Department nab other fugitives.

One such fugitive is Tom Billman. Accused of stealing more than $100 million from a Washington, D.C.-area S&L, Billman was apprehended in Paris last spring after leading the authorities on an around-the-world chase that lasted more than three years. At the time of his arrest, the globe-trotting embezzler was prominent on the U.S. Marshals’ 15 most-wanted list and living under an assumed name.

Rich’s contribution to Billman’s apprehension was to hire an Israeli private eye, the same Avner Azulay who checked out Rich’s girlfriend, to help track down Billman. With a hefty budget, Azulay paid out more than $200 an hour to private intelligence agencies in London, New York and Washington, instructing them to track Billman’s movements and money in Europe and Asia. The information that Azulay received was then provided to U.S. officials, and the rest (or, at least, Billman) was history. Whether Billman’s arrest was a direct result of Rich’s efforts is unknown. The Justice Department won’t say, and. Rich would under no circumstances want to take credit for helping the U.S. track down its enemies, some of whom are his business partners.

The contents of the second envelope are a mystery, but may have to do with rumors that Rich and Greenwald played a key role in arranging the 1992 expulsion of East German leader Erich Honecker from Moscow to Berlin, where, after an abortive trial, he was permitted (for reasons of health) to leave Germany for residence in Chile.

Asked about Honecker and Billman, Greenwald shrugs. “There are rumors,” he says with a sly smile. And then he shrugs again. “With Marc, there are always rumors.”

-30-

“King of the World,” was first published in Playboy in February, 1994.