“Did Richard Nixon—then Citizen Nixon—jump-start the Vietnam War on a secret mission to Saigon in 1964? The following piece suggests that he may have. The following story originally appeared in the anthology, Nixon: An Oliver Stone Film, edited by Eric Hamburg (Hyperion, New York, 1995).”

It is one of the most mysterious incidents in the Vietnam War, and I can’t get it out of my mind.

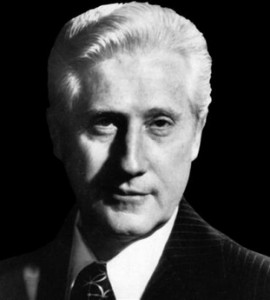

It was the spring of 1964, and the former Vice President of the United States, who was also the next President of the United States, Richard M. Nixon, was standing in a jungle clearing northwest of Saigon, negotiating with a man who, to all appearances, was a Vietcong lieutenant. Wearing battle fatigues “with no identification,” Nixon was flanked by military bodyguards whose mission was so secret that, when they returned to Saigon, their clothing was burned. [“Secret Nixon Vietnam Trip Reported,” New York Times, Feb. 17, 1985.]

At the time, Nixon had been out of public office (though not out of politics) for more than three years. After losing the Presidential election in 1960 and the California gubernatorial race in 1962, he’d gone into private practice as an attorney with the Mudge, Rose law firm, subsiding into what amounted to an enforced retirement from the world’s stage. It’s all the more surprising, then, to find this political castoff on a secret mission in the Orient – only a few months after the Kennedy and Diem assassinations.

Not that Nixon was a stranger to intrigue. On the contrary, his political career might easily be graphed as a parabola of Cold War conspiracies. As a Red-baiting congressman in the forties, he’d made the most of a lovely “photo opportunity” by uncovering stolen State Department secrets – in a Maryland pumpkin field. In the fifties, while Vice President, he’d run a stable of spooks – actually run them – in an off-the-books operation to destroy the Greek shipping tycoon, Aristotle Onassis. [Jim Hougan, Spooks (New York: Morrow, 1978), pp. 286-306. Onassis was targeted because of an agreement he’d reached with the Saudi government, monopolizing the export of oil from Saudi Arabia] In that operation, Nixon acted as a case officer to Robert Maheu (himself a linkman between the CIA and the Mafia) [Hougan, Spooks, pp. 286-300, and Donald L. Bartlett and James B. Steele, Empire (New York: Norton, 1979), pp. 282-285.] and a former Washington Post reporter named John Gerrity. Gerrity later recalled that “Nixon more or less invented the Mission Impossible speech, and he gave it to us right there, in the White House. You know the spiel, the one that begins, ‘Your assignment, gentlemen, should you choose to accept it. . . .” [Hougan’s interview with Gerrity.] Years afterward, when the Eisenhower Administration was drawing to a close, then Vice President Nixon served as the de facto focal point officer for the Administration’s plans to overthrow Fidel Castro. In that role, he was in regular contact with the CIA and with some of the darker precincts of the Pentagon.

It’s fair to say, then, that Richard M. Nixon knew what he was doing when it came to covert operations – but what was he doing in the jungle in 1964?

The story surfaced, briefly, some 20 years later, when the New York Times reported that Nixon, “while on a private trip to Vietnam in 1964, met secretly with the Vietcong and ransomed five American prisoners of war for bars of gold. : . .” [“Secret Nixon Vietnam Trip Reported,” p. 3.] In reporting this, the Times relied upon a report published in the catalog of a Massachusetts autograph dealer. The dealer was selling a handwritten note that Nixon had given to one of his bodyguards. The note read, “To Hollis Kimmons with appreciation for his protection for my helicopter ride in Vietnam, from Richard Nixon.”

The value of the note was increased by the circumstances that generated it, circumstances that Sergeant Kimmons described in the catalog:

When Nixon arrived at Ton Son Nhut Airport in Saigon, Sergeant Kimmons was assigned to security detail and was accompanying Nixon on all excursions away from the 145th Aviation Battalion where Nixon was staying. On the second day, Nixon dressed in Army fatigues with no identification and climbed aboard a helicopter with Sergeant Kimmons and a crew of four. [Fatigues typically have the owner’s last name sewn on a plaquet on the breast.]

They proceeded to Phuoc Binh, a village northwest of Saigon, where they met with Father Wa, a go-between that arranged the exchange of the gold for U. S. prisoners. The following day, Nixon and his party departed for An Loc, a village south of Phuoc Binh, where in a clearing somewhere in this area Nixon met with a Vietcong lieutenant who established a price for the return of five U.S. prisoners.

A location for the exchange was arranged and the crew departed for Saigon. Later the same day, the crew, this time without Nixon because of the extreme danger, departed for Phumi Kriek, a village across the border in Cambodia. A box loaded with gold bars so heavy it took three men to lift it on the helicopter accompanied the crew.

At the exchange point, five U.S. servicemen were rustled out of the jungle accompanied by several armed soldiers. The box of gold was unloaded and checked by the Vietcong lieutenant and the exchange was made without incident. The crew and rescued prisoners immediately departed for Saigon, and they were sent to the hospital upon their arrival.

Sergeant Kimmons’s mission was secret, and there were no written orders for his duty during this period. His clothes were destroyed as well as the film in his camera, and he signed an agreement not to reveal this incident for 20 years. Nixon’s note to him was hurriedly written at the conclusion of his assignment to guard Nixon on the following day. [The Times article quotes from a catalog printed by Templeton, Massachusetts, autograph dealer Paul C. Richards.]

That Nixon traveled to Vietnam in 1964 is a matter of fact. He departed the United States in late March on a round-the-world trip that took him, first, to Beirut, and then to Karachi, Calcutta, Kuala Lumpur, Bangkok, and Saigon. There, he dined with the American Ambassador, Henry Cabot Lodge, who had been his running mate in the 1960 Presidential race. In the days that followed, Nixon helicoptered into the countryside, [New York Times, Apr. 3, 1964] and then continued on to Hong Kong, Manila, Taiwan, and Tokyo before returning home. [RN: The Memoirs of Richard M. Nixon (New York, Touchstone, 1990), pp. 256-258, and article sin the following editions of the New York Times, covering his trip: March 23-28, 1964; March 30-31, 1964; April 2-10, 1964; and April 16, 1964.] Nixon later wrote that the purpose of the trip was to meet with Mudge, Rose clients and foreign leaders. Contemporary reports make it obvious, however, that the real purpose of the trip was to drum up international support for what was about to become America’s massive intervention in Vietnam. [Ibid.]

There is nothing in the Times’ account to suggest that the exchange of gold on April 3 was in any way relevant to the impending escalation of the war, but the possibility is an intriguing one. The Times’ article is anything but conclusive. On the contrary, it simply parrots the cover story that Sergeant Kimmons had been given, while at the same time neglecting to identify the mission’s middleman, the so-called “Father Wa.”

According to the Pentagon, which kept meticulous records of American prisoners of war, the POW release that Sergeant Kimmons described could not have occurred. The few Americans in captivity in 1964 were all accounted for in 1965—and most of them were still in cages. (Even so, we needn’t rely on the Pentagon to give the lie to Nixon’s cover story. Whatever else may be said about Richard Nixon, he was a consummate politician and, if he’d risked his life to rescue American prisoners of war, we’d have heard about it – if not in 1964, then most definitely in 1968.) As for the identity of “Father Wa,” Sergeant Kimmons (and the Times) fell victim to phonetics. Far more than an anonymous interpreter, the Rev. Nguyen Loc Hoa was a legendary figure in Vietnam. A bespectacled Catholic priest whose black cassock was usually cinched with a web ammo belt and a pair of holstered .45s, he was the symbol of militant anti-Communism in the south. [Cecil Currey, Edward Lansdale: The Unquiet American (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1988), p.220. ] Twenty years before, he’d fought a successful guerrilla war against the Japanese in China. Soon afterward, and as a colonel in the Chinese Nationalist Army, he’d battled Mao Tse Tung’s Communist insurgency. Driven from China, he and two thousand followers lived for a while in Cambodia before moving to a mangrove swamp in the Mekong Delta—where they set up a village and went to war against the Vietcong.

Father Hoa’s story was told in an article that appeared in The Saturday Evening Post, a few months after President Kennedy took office. Entitled “The Report the President Wanted Published,” the piece was published under peculiar circumstances. Authored by “An American Officer” whose identity could not be made public “for professional reasons,” [An American Officer, “The Report the President Wanted Published,” Saturday Evening Post, May 20, 1961, p. 31.] the article was in fact written by Gen. Edward Lansdale, an Air Force-CIA officer whose counterinsurgency theories and practice had inspired at least two books (The Ugly American and The Quiet American). [Currey, Edward Lansdale, p. 225.] According to. Lansdale, President Kennedy personally telephoned him to ask that he arrange for publication of what, until then, had been a secret report.

The article, and a follow-up piece that came out a year later, were blatant propaganda. [Don Schanche, “Father Hoa’s Little War,” Saturday Evening Post, Feb. 17, 1962. ] In sentimentalizing Father Hoa’s ferocious anti-Communism while demonizing the Vietcong, the articles did much to prepare the American public for the larger war to come.

Whatever President Kennedy’s motives may have been in pushing General Lansdale to publish his secret report, Nixon’s visit to the jungle is even more mysterious. Why should a former Vice President of the United States, accompanied by a legendary guerrilla fighter with excellent ties to the CIA, dress up in battle fatigues and adopt a cover story to facilitate a journey into the Vietnamese bush? The answer, obviously, is to make a very secret deal. But if, as we’ve discovered, Nixon was engaged in something other than ransoming prisoners, what was he buying with so much gold-and who were those guys that came out of the jungle near Phumi Kriek?

Recently declassified reports of the top-secret Military Assistance Command/Studies and Observations Group (MACSOG) raise the possibility that Nixon’s mission may have had to do with OPLAN 34-A. This was a covert operation to undermine the North Vietnamese by inserting “specially trained” Vietnamese commandos behind enemy lines. [“Once Commandos for U.S., Vietnamese Are Now Barred,” New York Times, Apr. 14, 1995, p.1.] The operation was run by the CIA from 1961 to 1963, and by the Pentagon from 1964 to 1967. We’re told that the activity was paid for with money the CIA had received from the U.S. Navy and then laundered offshore. [Ibid.]

Since Nixon’s mission had nothing to do with prisoners of war, it seems likely indeed that the Americans who dashed from the jungle at Phumi Kriek were CIA operatives or paramilitaries. This likelihood, coupled with the large amount of untraceable gold, suggests a mission of surpassing sensitivity – which, in turn, suggests OPLAN 34-A.

But what makes the incident at Phumi Kriek seem important, however, is not just the secrecy that surrounded it, or even the large amount of gold that was involved. It is, instead, the presence of Richard Nixon. Why him? What could such an outre politician have possibly brought to a covert operation in Vietnam?

The answer, of course, is nothing – except his face. Which is to say, the unmistakable face of American political authority. With Richard Milhouse Nixon present at the negotiations, and with the fabled Father Hoa as his interpreter, the supposed “Vietcong lieutenant” (himself, perhaps, a MACSOG operative) would never have questioned the legitimacy of the mission on which he was being sent. He would have known that, no matter how improbable, the mission was sanctioned by the highest echelons of the American government.

But what can that mission have been?

With Nixon, Hoa, and Kimmons dead, one can only speculate. But it’s worth noting that four months after the meeting at Phumi Kriek, OPLAN 34-A commando raids were carried out against the North Vietnamese in the Gulf of Tonkin. Two days later, an American destroyer, the Maddox, was attacked in the Gulf by North Vietnamese patrol boats – which led, almost instantly, to American air raids on North Vietnam and the passage of the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, escalating America’s involvement in the war.

In his recent mea culpa, [Robert S. McNamara, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam (New York: Times Books, 1995), p. 133.] former Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara writes that the attack on the Maddox was “so irrational” that “some believed the 34-A operations had played a role in triggering North Vietnam’s actions.” Though McNamara does not say so, his implication is clear: OPLAN 34-A operatives deliberately provoked the North Vietnamese and, in so doing, transformed “a small, out-of-the-way conflict into a full-bore war.” [“Once Commandos for the U.S. . . . ,” p. 1.]

If that is what happened, it’s understandable that OPLAN 34-A operations should be so secret that their very existence was omitted from the Pentagon Papers. [This, according to Sedwick Tourison, a Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) analyst, who called OPLAN 34-A operations “the secret” of the Vietnam War (“Once Commandos for the U.S….,” p. 1). ] What’s less clear is whether or not Richard M. Nixon was directly involved in the secret funding of operations that may well have jump-started the Vietnam War.